Telefon: 08‑5195 5488

E-post: info@visarkiv.se

Besöksadr: Torsg. 19, Stockholm

- Virtual Assyria

- Preface

- The Assyrians as an example

- Assyria – your land in Cyber Space

- Cyberland – Music, Nationalism & the Internet

- With music as a boundary marker

- Christians from the Middle East

- The liturgy of the Syrian churches

- A visit to a musical rebel

- Assyrian music on the Internet

- Expressive specialists

- References

A visit to a musical rebel

"You've got a visitor, Gabriel, a swedoyo, a Swede, who is interested in your music. He's come to do an interview."

At first there was complete silence. After a while the old man in the bed muttered something inaudible in answer and raised himself on his elbow and peered out over the room. "Shlomo – Welcome. Come and sit near me so that I can see you."

The person that we had come to visit in the nursing home in Rinkeby in Stockholm's northern suburbs turned out to be a very old man. People had told me about a man from Qamishli in Northern Syria, a vivid character and a determined musical rebel, who was now living the remainder of his days in security in Sweden, far from Middle Eastern conflicts. And here he lay, haggard and emaciated and apparently alone, in a Swedish hospital bed. He raised a bony hand in greeting, as though to show that he knew we were in the room. Gabriel Assad died not long after my visit.

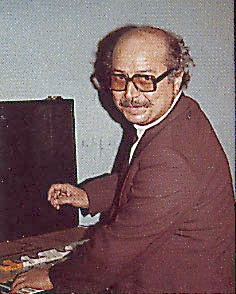

Gabriel Assad in his workroom at the Cultural Centre in Qamishli.

Source: the Assyrian magazine Hujådå

Gabriel Assad, or Jubran Some as he was baptised, was born in 1908 in Midyat in Tur'Abdin, in what is now South East Turkey. Like many other Christians from Syria, Gabriel Assad had two names. The surname Assad, by which he is known among his friends, is a family name – his father's Christian name. The second surname, Some, is his "official" surname which is mainly used in contacts with authorities.

During the outbreaks of violence and the wholesale murders of Christians in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, the family fled to Damascus, where they lived under relatively stable conditions. The father had a steady income as a merchant in the town.

When it came to choosing a profession young Gabriel had other plans however: his dream was to be a musician. But the musical profession was definitely not a common choice or even a fitting one for a young Syrian Orthodox Christian at that time. All types of profane music-making were condemned by representatives of the church. Music-making in contexts other than activities organised by the church was considered a sin.

Nobody in the Some family had ever gone in for music before. Despite this Gabriel's parents accepted their son's wishes. Even if they were not happy about it, they let him take lessons in Western art music. And it was also in Western art music that Gabriel Assad found his first musical models.

Many of Gabriel Assad's compositions have become standard tunes for Assyrians. The example above is taken from Chamiram Khouri's book "The Cluster of the National Songs", an anthology of songs which to a large extent have been written by Assad.

The power of the church over its members was not as wide-ranging in Syria as it was among the farming population in Tur'Abdin. This applied particularly to the larger cities in the Middle East and the Eastern Mediterranean region. Profane music-making was common both among the Christian and the Muslim populations of Damascus, Aleppo, Smyrna, Istanbul, Cairo etc, all of which were modern cosmopolitan cities (see the section on the musiqa tradition in Aleppo below). The move from Tur'Abdin to Damascus was therefore an important prerequisite for Assad's musical activities.

Listen to an excerpt from Gabriel Assad's composition Forah tho with (I was a wing-clipped bird).

The sheet music of Forah tho with.

Source: Hammarlund 1990

The music is characterised by the contrast between the "oriental" melodies and the Western accompaniment. This mixture of East and West is typical of a large proportion of Assad's output, and is also symptomatic of the prevailing cultural and political situation in Damascus in those days.

The musical environment in Damascus at that time was some what complicated.

The Christian minority had their church music, whose roots went back at least as far as the first Christian churches in the region in the second century. There was also folk music, of course, which was partly common to other people in the region; Kurds, Turks and Arabs. In addition to these genres there were other musical spheres to which other people in the region had access in the first instance: Persian, Arabic and Turkish art music, for instance, as well as different types of popular music.

Traditionally, Turkish and Arabic art music have had powerful strongholds in larger cities in the Middle East. Damascus, Baghdad and Aleppo were all important centres for high culture in the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Ensemble in Aleppo in the middle of the 18th century.

The picture is taken from the article The Natural History of Aleppo, which was written by Alexander Russell in 1754. (Source: Turkish Quarterly, vol. 5/6, 1993).

Russell's comments on the musicians in the picture are of particular interest. The def-player on the left is "a Turk of lower class", which, according to Russell, can be deduced from his rather clumsy turban, among other things. The next person is a Christian tambour-player, and next to him is a ney-playing dervish. The fourth person, who is playing the fiddle or kemenge, is also a Christian of middle rank. Russell does not know anything about the fifth person, but he mentions that the man is probably a Turk, judging from his clothing.

The colourful mixture of Christian and Muslim musicians of different social status was not only characteristic of the musical world, but of the Ottoman Empire as a whole. The Turkish Empire was in fact characterised by linguistic, religious and ethnic compounds to a much greater extent than is usually realised. The ruling classes consisted of Turkish military officers, members of the priesthood of the Orthodox Church, Jewish and Greek merchants and bankers, scholars and writers of Persian, Arabic, and even Balkan origin and others. It was not until the 16th and 17th centuries that the Ottoman upper class came to be dominated by Muslims.

We cannot be completely certain that the Christian musicians belonged to the Syrian Orthodox church, considering its ban on profane music-making. At the same time, as mentioned above, we know that the church's negative attitude towards profane music did not have the same impact in Aleppo as it did in rural areas. Russell also notes that the Christian tambour-player is slovenly dressed.

When Russell describes the music of 18th century Aleppo, he distinguishes between outdoor music, which was played on shawms and drums (cf. folk music and dance below), and indoor music, which was played by ensembles like the one in the picture (cf. Lundberg 1994). Indoor music appeals more to him than the "shriller" outdoor music and he writes:

The chamber music consists of voices accompanied with dulcimer, a guitar, the Arab fiddle, two small drums, the dervis's flute and the diff, or tambour de Basque. These compose no disagreeable concert, when once the ear has been some what accustomed to the music; the instruments generally are well in tune, and the performers, as remarked before, keep excellent time (Russell 1754 reprinted in Turkish Music Quarterly: 1993).

The place of music in society

Like the Some family, a large proportion of the Syrian Orthodox population in Damascus had roots in Tur'Abdin. The musical means of expression at their disposal also originated in this region. These included folk songs in Turoyo as well as instrumental music, mainly played on shawms, mashroqo and bass drum, dawole (cf. zurna and davul). This instrumental music primarily functioned as dance music and was played by musicians from groups other than Syrian Orthodox Christians. This practice – that profane dance music was performed by musicians who were not part of the group – is a common occurrence in the region and is not related to the Christian culture. Both ethnic Turks and Arabs often left instrumental music-making to Gypsy musicians (here the term Gypsy has often been used to denote other folk groups, not just "ethnic" Gypsies). The Islamic religion also has an ambivalent attitude to music and music-making, both of which are considered a sin according to certain parts of the religion.

Still today there is a scarcity of folk musicians in the Assyrian group. Even if a mashroqo-player is not regarded as a sinner, musicians in the folk music sphere are associated with zutoye, the lowest class of people in Assyrian/Syrian society. To answer the need for traditional folk music at weddings and other traditional occasions, musicians from other ethnic groups from the same region have to be hired. In Sweden the Turkish zurna-player Ziya Aytekin has played at a large number of Assyrian and Syrian weddings. The dearth of musicians also means that folk musicians with Assyrian backgrounds, such as the Sado family from Armenia, have a crucial role in the production of records, for example.

Listen to an excerpt from a suite of folk dances.

The suite Raqdo d'Shekhane comes from the cassette "Assyrian Folk Music" with the Sado brothers, issued by the Nineveh Music Association in Gothenburg. Nowadays the mashroqo and the dawole can be replaced by synthesizer and drum machine. Listen to the musician Nabu Poli from the group Qenneshrin when he plays "mashroqo" on his keyboard.

When Christians from Tur'Abdin fled from the Ottoman Empire over the border to Syria in connection with the outbreak of violence and massacres during the First World War, the new rulers – the Frenchmen and the British – were regarded as liberators.

This attitude was probable reflected in Gabriel Assad's choice of musical training. The status of Western music was higher than that of his native folk music, and it also represented forces in the political power game in the Middle East which were not regarded as hostile by the Christians. Arabic and Turkish art music dominated the musical environment, however, parallel with popular music which at that time was becoming increasingly prominent.

Nevertheless, when the young Gabriel Assad hoped to make a living as a musician, he started out in the domains of Arabic popular music.

Urban popular music forms which developed in the Mediterranean region during the 19th century experienced a new boom in the early 20th century. As before, the music belonged in restaurants and night clubs and the style can be described as a mixture of Arabic/Turkish melodies and modes and Western music ideals. The musicians also experimented with Western instruments and forms of expression.

An early impulse was provided by the interest in oriental dance in Europe and America towards the end of the 19th century. The success of dancers like "Little Egypt" in America was also echoed in parts of the Arab world. Belly-dancing in the so-called "cabaret style" was a common feature at many restaurants, cafés and night clubs throughout the Eastern Mediterranean region in the 1920s. Cosmopolitan cities such as Cairo and Beirut became centres for this new type of entertainment. At the end of the 1920s Gabriel Assad moved to Beirut and was taken on as a violinist at one of the town's "casinos", which was the name used for restaurants and night clubs with live music and dance (cf. Turkish "gazino").

Listen to another of Assad's compositions, Num habib num ni, the lullaby "Sleep My Darling Sleep", from the same record as "Forah tho with" above.

Gabriel Assad on stage together with the present president of the Assyrian National Federation, Ablahad Lahdo. The photo was taken in Qamishli at the beginning of the 1970s.

Source: the magazine Hujådå

Today Gabriel Assad's handful of followers are spread out all over the world. From a musical perceptive his closest disciple is the composer and conductor Nouri Iskandar. Today Iskandar works in Aleppo in Syria. His compositions, like Assad's, are characterised by a mixture of East and West. The melodies are characterised by the same modal structures that can be found in Syrian Orthodox church music and also in the Arabic maqam music. The harmonies and instrumentation are in Western style, however.

Source: the cassette "Oriental Music" by Nouri Iskandar. Nineveh Studio.

Listen to Nouri Iskandar's composition for lute (oud) and string trio.

Or why not a piece for solo violin and string quartet?